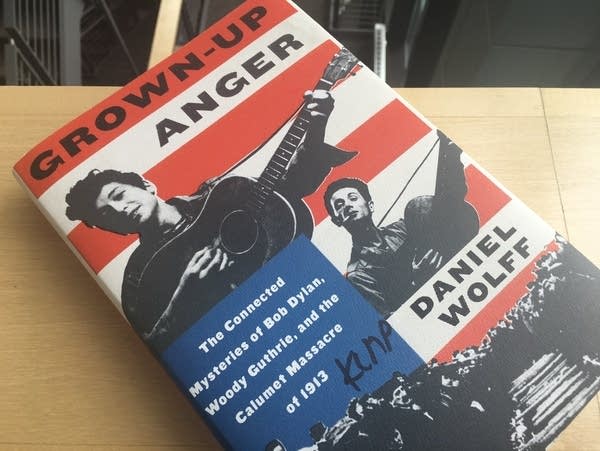

Rock and Roll Book Club: Daniel Wolff's 'Grown-Up Anger'

by Jay Gabler

July 26, 2017

Daniel Wolff's moving new book Grown-Up Anger is subtitled The Connected Mysteries of Bob Dylan, Woody Guthrie, and the Calumet Massacre of 1913.

What was the Calumet Massacre of 1913? Woody Guthrie wrote a song about it, but it's not one of his best-known numbers, and you'd have to be a pretty serious Woody Guthrie fan to recognize it. Bob Dylan, of course, was a pretty serious Woody Guthrie fan — and he played the song as early as his days in Dinkytown.

The Calumet Massacre was an incident that took place at the Italian Hall in Calumet, Michigan on Christmas Eve 1913. Local copper miners were in the heat of a contentious strike, and the local Ladies' Auxiliary tried to cheer everyone up by throwing a Christmas party. At one point, a panic broke out and 400 people occupying the social room on the hall's second floor all tried to escape down a single six-foot-wide staircase.

There was a pile-up near the door, and 73 people died in the crush: 11 adults and 62 children, all smothered to death in less than three minutes. Tiny trenches marked the spots on the wall where dying children had frantically tried to claw their way free.

Wolff calls the incident a "mystery," because key elements of the story remain unknown. What caused the panic? Multiple attendees agreed that a man ran in and yelled, "Fire!" despite the fact there was no actual fire. The canonical version of the story among labor organizers, the reason the incident became known as a "massacre," was that the man who yelled was sympathetic to the mine owners. What's more, many mining families believed that company sympathizers actively held the exit doors shut.

The true identity of the man, though, is unknown. It's also possible that no one was holding the doors shut — that the blockage was simply caused by people tripping and falling, causing a chain reaction when others tried to climb over them and got stuck.

Why does that incident — relatively obscure, even for historians and fans of Guthrie and Dylan — become the centerpiece of Wolff's book? Wolff, a music historian, suggests that the very ambiguity of the disaster makes it an apt pivot point for understanding what "folk" and "protest" music meant in the 20th century. It was unambiguously a tragedy, amidst obvious economic injustice, but whether it was a deliberate "massacre" remains unknowable.

In alternating chapters, Wolff tells three asynchronous stories. The oldest story is the history of mining and industrialization in Michigan — particularly in the Keweenaw Peninsula area, a rich source of copper deposits that were exploited in an effort led by Harvard's vaunted Agassiz family. The Calumet & Hecla Mining Company became the villain of the song written by Guthrie, who was just one year old when the Italian Hall disaster happened.

Wolff's second story is that of Guthrie, who grew up amidst a tumultuous family life in Oklahoma. His father was a racist real-estate shark who ended up running a brothel after he went bust, while his mother had Huntington's disease and was hospitalized from the time Woody was 14. Eventually Guthrie developed an interest in music and made his way to California to become a hillbilly singer. Instead, he became a "folksinger."

The changing meaning of what, exactly, it means to be a "folksinger" provides much of the meat of Wolff's history. Guthrie started out as a purveyor of early string-band music by the likes of the Carter Family, but his original and adapted songs added increasingly pointed political messages. The Woody Guthrie discovered by Bob Dylan in the early 1960s, when Guthrie himself had been hospitalized for years with his own case of Huntington's, was a man who wore authenticity like a badge — although his songs were more authentic to his own personal views and experience than to any single "folk" tradition.

One of the points Wolff drives home is that Dylan's own Minnesota background was significant in this regard. Hibbing, on the Mesabi Iron Range, was a hotbed of labor organizing and political disputes. Dylan didn't "get political" in New York: labor agitation had been the backdrop to his entire youth, although his own appliance-merchant family sat somewhat on the sidelines. Dylan himself described northern Minnesota as "an extremely volatile, politically active area — with the Farmer Labor Party, Social Democrats, socialists, communists."

Wolff also points out that, by the time Dylan was launching his music career, "folk music was pop music." Groups like the Kingston Trio were having top ten hits with tracks that, far from being legitimately "traditional," took newfangled rock-and-roll songs like "Tijuana Jail" and dressed them up in old-timey clothing. By aping Woody Guthrie, Dylan was at once hopping a trend and bucking it.

The career path that took Dylan from "1913 Massacre" to "Like a Rolling Stone" is one that Wolff sees as poignantly encapsulating the way that the entire 20th century took the world — and art along with it — from specific grievances to global angst. Guthrie's songs, and Dylan's earliest songs, are full of specific references to incidents, people, and places. There's a sense that we know who the enemy is: it's that guy who shouted "Fire!" in a room full of children. It's the mining company. It's William Zanzinger, who killed poor Hattie Carroll.

By the time Guthrie died, though, he'd seen a war against fascism yield to an America that blacklisted anyone seen as "communist." Dylan's early career saw the moral clarity of the Civil Rights movement, but also the morass of Vietnam. Was President Johnson the enemy, or an ally? Who's Mr. Jones? Who's the "you" being excoriated in "Like a Rolling Stone"? Many of the most compelling interpretations suggest that the song's addressed to Dylan himself.

You might not know "1913 Massacre," but you probably know "This Land is Your Land." Guthrie's most universal anthem, it was also, as Wolff notes, an answer song: a response to Irving Berlin's "God Bless America." That show, a radio hit in the lead-up to the Second World War, was embraced by the descendants of European immigrants — but Guthrie heard it as a song that invokes a deity to justify a profoundly unjust status quo.

"This land is your land," he sang, addressing his song to those who wander, those who struggle, those who feel lost. He borrowed his tune from a Carter Family hymn, which assures us that all will be made right on Judgement Day. "Guthrie plays off that," writes Wolff, "insisting we don't have to wait till then for the world to get better and we don't have to pray to God to make it happen; there's already a voice around us, sounding."

Like Dylan, he was singing to himself.