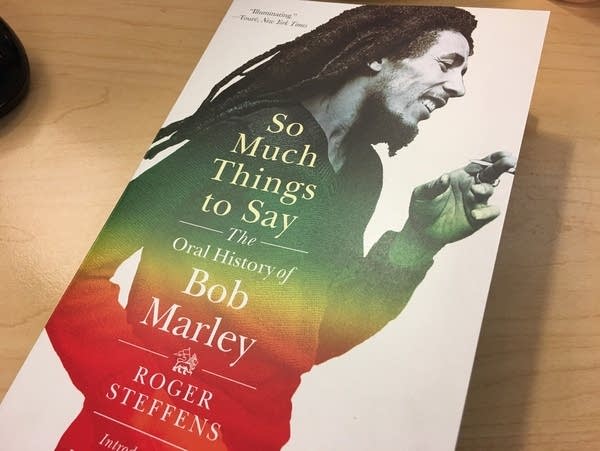

Rock and Roll Book Club: 'So Much Things to Say' tells the Bob Marley story

by Jay Gabler

November 07, 2018

Say what you will about Roger Steffens's oral history of Bob Marley, it has the right title. A lot of people, indeed, have So Much Things to Say about reggae's definitive superstar and his very complicated life.

First published last year in hardcover, the book was greeted with jubilation by hard-core Marley fans. Rolling Stone calls it a "landmark." Decades in the making, the book was assembled (and much of it written, as a contributing "voice") by Steffens, who championed Marley on his KCRW reggae show before hardly anyone in America had heard of him. He was tireless in pursuing Marley intimates; his sources include Bunny Wailer, Peter Tosh, Rita Marley, and many more.

If you're one of Marley's many superfans, and you've read one or more of the hundreds of books already published about him, you'll be glad for Steffens's authority and attention to detail. A responsible historian, he often airs multiple competing versions of events, then tries to adjudicate among them. In a preface, he admits that he chose not to focus on the best-documented aspects of Marley's life, preferring to dig into the unanswered questions.

There are sure a lot of those.

How did Marley's legendary first group, the Wailers, break up in 1974? The short version is the same old story, creative tension. The long version is...in the book.

Who was behind the Dec. 3, 1976 studio shooting that left Marley performing at the free Smile Jamaica concert with a bullet in his arm? The short version is, it was probably politically motivated. The long version is...in the book. (The event was also fictionalized in Jamaican-Minnesotan author Marlon James's acclaimed 2014 novel A Brief History of Seven Killings.)

How did Marley die, and what did it have to do with a toe injury he sustained while playing soccer under the Eiffel Tower? The short version is, the injury revealed a symptom of melanoma, of which Marley had a family history. The long version, multiple chapters' worth, is...in the book.

While the book will be tough going for a casual fan, there are things that anyone can take away from the book. For one thing, it reveals just how collaborative Marley's music was. His wasn't a self-contained musical genius like Prince's; from the beginning, he was the artist to come out of Jamaica's creative ferment with the talent, the charisma, and the vision to take reggae global. His bandmates Bunny and Peter were key contributors to the Wailers' early music, though. Although "Bob Marley and the Wailers" may have eventually seemed synonymous with just "Bob Marley," they were originally a true band, and Marley always benefited from strong collaborators.

That makes this a busy book even before considering Marley's crowded personal life. He and Rita married young, and any ideals of lifelong commitment seem to have been very short-lived. While they remained married (as well as collaborating musically) until Marley's 1981 death, both had other lovers, some short-term and others long-term.

The stories of Marley's early life are both fascinating and harrowing. We learn that his father, a British white man who ducked out early and died when Bob was just ten, left him as the subject of frequent scorn in his community and even in his neighborhood. We learn about how turbulent life in Jamaica was, and Marley's lifelong commitment to his country even under adverse circumstances.

As Rolling Stone notes, Rita's is the voice we'd like to hear more of. In one incredibly painful story, Wailers singer Beverley Kelso describes witnessing Tosh raping the future Rita Marley. Kelso didn't tell the story to anyone until she spoke with Steffens in 2003. (In her own memoir, Rita Marley would write that Bob Marley also forced himself on her.)

The roles of mentor-turned-competitor Johnny "I Can See Clearly Now" Nash, label owner Danny Sims, legendary producer Lee "Scratch" Perry, and Island Records founder Chris Blackwell are elucidated. There are moving descriptions of Marley's trips to Africa (Betty Wright remembers dancing in Gabon to "Jamming"), including this anecdote from photographer Bruce Talamon.

One morning Bob was walking along the beach and this young man came up to him and challenged him: "What's this Rasta stuff? What do you mean coming to Africa, telling us about Africa?" The kid wanted him to tell them more. Bob took his time and explained to them about his excitement being there and also about the black diaspora, you and me are the same, I'm a black man from Jamaica, you're from Africa, we all come from Africa.

Some chapters are very dense; for example, a chapter on how exactly Marley balanced his calls for peace with calls for Africans to unite and fight for independence. The answer gets deep into African politics of the '70s, involves translation of patois, and of course features competing voices.

In the end, for all the complications surrounding Marley's life music, he remains now what he was then to so many: an inspirational icon who contained multitudes. Steffens notes that he actually displayed his wounds to the audience at the Smile Jamaica concert, singing a capella next to his wife who also had a bullet lodged in her skull.

"What," he asks rhetorically, "can you possibly compare that to?"